A few years ago, I explored one of the popular online learning platforms, and found two music courses. I don’t remember the exact names of the courses, but one was called something like “Developing Your Musicality”, and the other was titled “The Basics of Music Theory” or something like that. The first course was designed and taught by an actual bluesman. He played a lot of beautiful improvisations in that course. He taught the students how to listen to music and enjoy it. He encouraged the students to explore music, and the tests in that course were either about performing and recording simple music tasks or finding pieces of music that would illustrate theoretical statements in the videos. Thanks to that course, I actually started playing piano again without feeling stupid or pathetic (if you went to music school you know what I am talking about).

The other course was designed and delivered by people in academia. They warned us from the very beginning that that course wouldn’t help anyone to become a better musician. The course mainly explained different musical modes, intervals, chords, and cadences. The tests and quizzes in that course were all about terminology. I got bored very quickly and quit after a couple of weeks.

Unfortunately, language courses in educational institutions often look like the latter example. Speaking a new language is a performing art, but language textbooks are full of theoretical information and linguistic terminology.

Please, don’t get me wrong, I don’t mind linguistic terminology. I acknowledge and respect its explanatory power. I have a master’s degree in linguistics, and I am familiar with linguistics concepts and its terminological apparatus. Did that knowledge help me to become more fluent in English? No. I became fluent in English because I spoke it daily with my colleagues when I worked in an international company. Before that, I listened to British and American rock musicians, watched movies in English, read books in English and so on. A musician excels through mindful practice, and so does a language speaker.

There are many similarities between acquiring a new language and acquiring a new musical instrument. Both skills totally rely on regular practice. You can’t learn how to play piano by listening to lectures about playing piano, you need to actually put your hands on the keys and play. Slowly, painfully awfully, but play. You won’t start speaking a new language after reading a textbook about it, no matter how thick and brilliant the book is. You need to produce something in that language in order to become a speaker eventually.

Every musician was horrible at the beginning. Even famous prodigies performed poorly when they just started learning the instrument. Every language learner starts with speaking horribly, but there is no other way into language fluency.

Pianists know that “knowing” what key to press in a specific moment doesn’t mean that you won’t press the wrong key accidentally. Musicians practice to make the muscle movements automatic. Yet, I often hear from language learners, “Gosh, I know this word! I learned it! Why did I forget it?” Language learners “know” much more words than they can actively use in their spontaneous speech, this is just normal. The goal of language practice is exactly to make the process of putting your thoughts into words smooth and effortless, as automatic as a virtuoso’s fingers gliding through the keyboard.

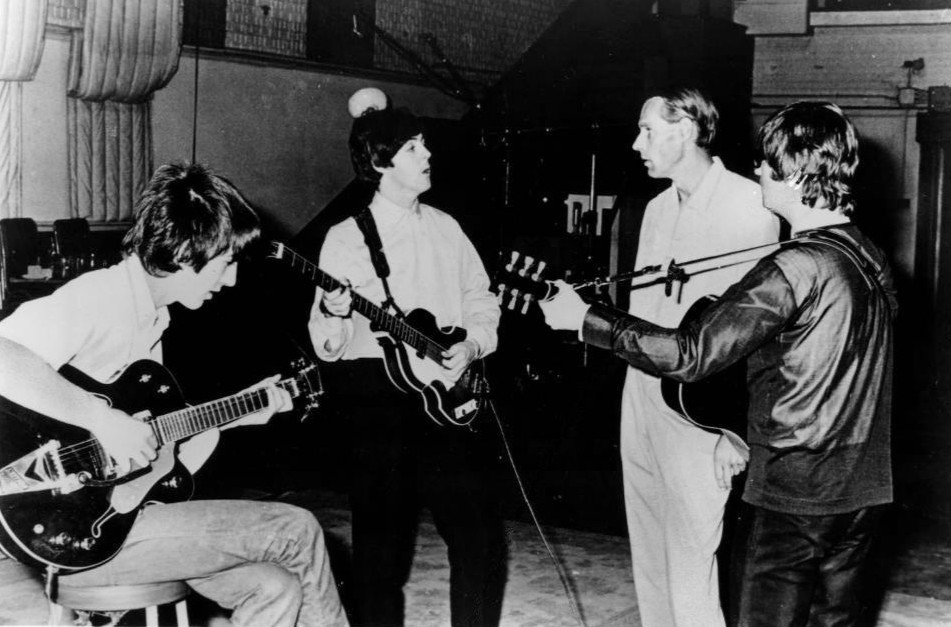

Should language learners study grammar and theoretical linguistics? Well, some world famous musicians never learn music notations. The legend has it that the Beatles never learned how to read scores. Most musicians, however, went to music schools. Mind you, we can’t attribute their success to the music schools solely. Some people acquire a new language by simply communicating with native speakers. As a language teacher, I have noticed that my students usually reproduce the vocabulary, phrases, and grammar structures they learned from communicating with native speakers faster and better than the phrases and vocabulary they learned through studies. Some knowledge of grammar never hurts, but it won’t make you a fluent speaker.

If you think about your language studies as about learning a performing art, you’ll adjust your expectations. You’ll understand that getting nervous in front of native speakers is normal, as well as feeling a gap between what you want to say and what you are able to articulate when actually talking. There is a huge difference between the beautiful music in my head and the noise my clumsy fingers are making — this is a part of learning.

When I finished that first online course, I said to myself that I would try my very best to make my Russian lessons similar to it: encouraging and inspirational. As a teacher, I see my goal as picking my students’ curiosity and showing them ways they can enjoy using the language, so that they would want to practice without even thinking that they’re practicing Russian. I think I manage to avoid temptations to switch to linguistics jargon in my classes, at least, most of the time. Most importantly, I hope that my students leave my classes with the desire to do something in the language they’re acquiring, because this is when the real acquisition happens.

Featured Image: Duet by Maria Pavlova