Do you like the movie “101 Dalmatians”? I love it, and not just because of the adorable puppies. The Russian title of this film—”Сто один далматинец”—perfectly illustrates one of the most bonkers areas in Russian grammar: number-noun agreement.

Think about it. In English, we say “101 Dalmatians” because, well, there are clearly more than one puppy running around. But in Russian? The word for dalmatian (далматинец) stays stubbornly singular. Why? Because 101 ends with 1, and in Russian, any noun after a number ending in 1 must be singular.

I know. It makes no sense.

This is just one of many rules that govern counting in Russian, and honestly, if you can find any logic in this system, please enlighten me because I’m convinced it’s the most irrational thing a living language could come up with.

The Rules

Number One

In Russian, один (one) is technically an adjective, which means it has to match its noun in gender and number like some sort of grammatical chameleon:

- один далматинец (masculine)

- одна собака (feminine)

- одно кино (neuter)

- одни двери (plural-only nouns)

The noun stays in nominative singular, which actually makes sense—there’s only one thing to count.

Numbers Two to Four

Два, три, четыре (2, 3, 4) take genitive singular. Think of it as “two OF something”: два далматинца, три собаки, четыре окна.

Quick note: два becomes две when counting feminine nouns, because apparently even numbers have trust issues in Russian.

Numbers Five and Up

From 5 onward, everything takes genitive plural: пять далматинцев, семь собак, девять окон.

I tell my students that ancient people could only count to 4 (1, 2, 3, 4, many), so when we hit 5, we panic and switch to plural. Is this historically accurate? Probably not. Does it help remember the rule? Absolutely.

This genitive plural continues all the way to 20: одиннадцать далматинцев, пятнадцать собак, двадцать окон. I’ve noticed many languages treat numbers 10-20 differently—maybe there really is something to this whole “ancient counting” theory.

Compound Numbers: The Plot Twist

Here’s where it gets fun. For numbers like 21, 32, 56, you ignore everything except the last digit:

- 21: nominative singular (because it ends in 1)

- 22-24: genitive singular (because they end in 2-4)

- 25-29: genitive plural (because they end in 5-9)

This is exactly why “101 Dalmatians” becomes “Сто один далматинец”—that final 1 calls all the shots, even though there are clearly 100 other dalmatians involved.

Zero

And then there’s ноль (zero), which represents the complete absence of anything, yet somehow takes genitive plural. Because apparently even nothingness needs to be grammatically complicated in Russian.

How Do Russians Cope?

Here’s the thing: most native Russian speakers have never noticed these rules are weird. In my experience, only two groups of Russians ever stop to think “wait, this is bonkers”—teachers of Russian as a foreign language and programmers.

Back in the early days of computing, Russian programmers had to explain these rules to computers. Instead of the simple English “add -s if there’s more than one,” they had to write lines and lines of code describing all these bizarre conditions.

The Bottom Line

If you’ve been studying Russian for a while, you’ve probably encountered these counting rules before. As the ancient Latins said, “Repetitio est mater studiorum” (or “Повторенье – мать ученья” in Russian)—repetition is the mother of learning.

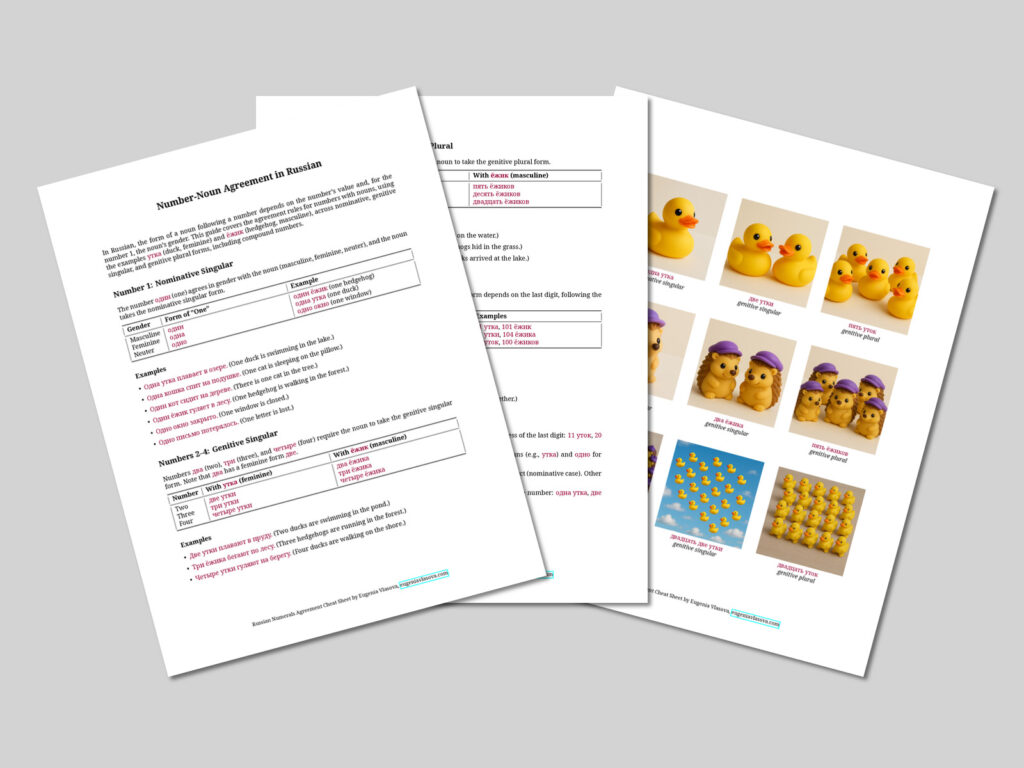

I’ve created a cheatsheet that breaks down all these rules with examples, so you’ll never again have to wonder whether your dalmatians should be singular or plural. You can grab it from my shop and keep it handy for those moments when Russian counting makes you question your life choices.

Got any tricks for remembering these rules? Share them in the comments—I’m always looking for new ways to help my students (and honestly, I’ll probably steal your ideas for my lessons).

Until next time!