What Makes Up Russian Pronunciation: Consonants

In the previous article, I wrote about why pronunciation is more difficult to learn than grammar, and why many academic courses fail to teach proper pronunciation. In this article, I’m going to describe the specific features of the Russian phonetic system—what actually makes speech sound like Russian.

Each language has its melody. Even without knowing a single word, you probably can tell if people are speaking French, Mandarin, Hindi, Russian, or German. Even if you can’t pinpoint an overheard conversation to something specific, you can probably guess if it’s “something Slavic” or “some sort of Arabic.” This is possible because each language has a phonetic profile, a set of features that make up its acoustic image. Some actors and stand-up comedians even imitate these sounds without saying real words. One famous example is Adriano Celentano singing total gibberish in what others perceived as “American English.”

Russian, like any other language, has a few features that define the way it sounds. First of all, in Russian, consonants play a more important role than vowels. (In academic lingo: “Russian is a consonant-centric language.”) Consonants in Russian are more nuanced. They determine how the following vowel should sound. Native Russian speakers hear differences in articulation of consonant sounds better than English speakers. Master your Russian consonants, and 80% of the job is done.

Voiced and Voiceless Consonants

Russian consonant sounds can be voiced and voiceless. This feature is not unique – many languages have pairs of voiced-voiceless consonants (b and p, d and t, v and f, and so on). If you recall comedians mocking Russian, you probably remember that they try to sound aggressive. Well, probably Russian makes this impression because it is a “prevoicing” language. When a voiced consonant is released, the vocal folds are already vibrating, so acoustic voicing is present from the very beginning of the audible consonant portion. This robust beginning of consonant sounds is at least partially responsible for the bad reputation of the language. English doesn’t do prevoicing, and overall, English vocalization seems weaker to the Russian ear – if audible at all.

There is a catch with Russian voiced and voiceless consonants, though. Voiced consonants at the end of words or before a voiceless consonant devocalize. That is, they lose their voice. In English, you articulate /g/ in dog and /d/ in God, but in Russian the final letters in these words would change to /k/ and /t/ respectively. If you have Russian friends, you’ve probably noticed that they never put enough voice into the final consonants—this is because in Russian, it is mandatory to devocalize them. It works like a reflex, an unconditional one: you just don’t vocalize endings, that’s it!

This is also true for clusters of consonants where voiced consonants precede voiceless ones – in this case, they both become voiceless. You do not switch from voice to no voice in two consecutive consonants. For God’s sake, vodka is /votkə/, not /vɑdkə/!

In turn, voiceless consonants in Russian can get vocalized if the next consonant is voiced. It must be very funny for English speakers when Russians say foodball instead of football, but this is exactly what the Russian language does: when two consonants are together, the latter affects the former—the former consonant accommodates vocalization (regressive assimilation).

Practical takeaway: Voiced and voiceless sounds change when at the end of a word and in a consonant cluster. Remember to devocalize and vocalize retrospectively.

Hard and Soft Consonants: The Real Challenge

When you voted in my poll about Russian pronunciation difficulties, many of you identified hard and soft consonants as your biggest struggle. You were absolutely right — this is where most learners have the deepest, most persistent problems.

All consonant sounds in Russian are either hard or soft. The words “hard” and “soft” don’t explain anything, and linguists prefer to call them “palatalized” and “non-palatalized.” This is a more accurate description because you can’t touch a sound and tell whether it is hard or soft, but you can tell whether your tongue goes towards the palate (hence, palatalized) when you articulate a consonant. Most consonants in Russian go in hard-soft pairs, but unfortunately, both hard and soft consonants in each pair are displayed with the same character. You can’t tell if a consonant is hard or soft by just looking at the character. You really need to know when to “palatalize” a sound.

Being able to hear the difference between similar hard and soft sounds and reproduce them is the key to good Russian pronunciation. There are many words that differ only by one hard/soft consonant:

- Мат (obscene words) vs мать (mother)

- Угол (corner) vs уголь (coal)

- Кров (shelter) vs кровь (blood)

- Вес (weight) vs весь (entire)

- Лук (onion) vs люк (manhole)

- Рад (glad) vs ряд (row)

And so on.

Hard consonants are usually followed by А, О, Э, У, Ы, and soft consonants are followed by Ь (hence the name: soft sign), Я, Ё, Е, Ю, И. Hardness and softness do not “contaminate” nearby consonants in consonant clusters, so some tongue gymnastics is unavoidable.

Though you may think this distinction is nothing but a subtle nuance, Russians hear it very well and can tell whether you are native or not by how precisely you palatalize consonants. And, by the way, the difference between Ш and Щ is exactly the difference between hard and soft consonants: Ш is hard, and Щ is its soft counterpart.

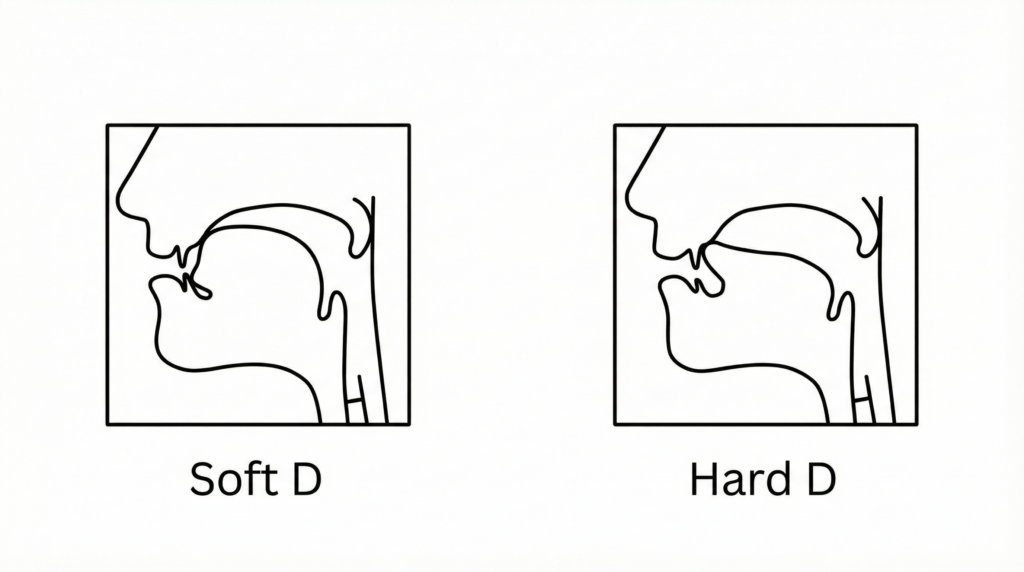

What Actually Happens When You Make a Soft Consonant?

But what exactly do Russians do when they pronounce a soft consonant? This is the million-dollar question. Russian academic works don’t really bother to dig into that because, well, for native Russian speakers it is rather obvious: a hard consonant is hard, and a soft consonant is soft. (Why? Can’t you hear that?) For decades, Russian as a foreign language textbooks have been explaining that “to make a soft consonant, raise your tongue towards your palate.” I’ve never seen a single Russian learner who found that explanation sufficient or helpful.

When inquisitive linguists used X-ray and ultrasound devices, they discovered that the Russian tongue root position is somewhat retracted for hard consonants. One widely accepted hypothesis is that Russian articulatory posture (the way Russians hold their speech organs) requires the tongue to be retracted for hard consonants and sounds like “ы.” (Is that your most dreaded sound?)

Newer research suggests that soft consonants involve an advanced tongue root. It seems that what actually happens in Russian mouths when they say “щи” or “лень” is that the base of the tongue moves about a quarter to a half inch forward. That causes the whole body of the tongue to move up, so the middle of the tongue does indeed rise towards the palate. But the whole motion starts from the root of the tongue. The retracted position of the tongue is somewhat neutral for Russian—the basic one. You probably didn’t know that humans can move “the root of the tongue,” whatever it is, forward, but—well, it is possible. And Russians do that without giving it much thought.

My good friend, who is a linguist and an American English voice coach, suspects that the tension many English speakers perceive in the Russian accent is simply the result of those muscles under the tongue being always toned and ready to move, which I as a native speaker can confirm.

The Bottom Line

All Russian consonants are either hard (non-palatalized) or soft (palatalized). You can tell whether a consonant is hard or soft by looking at the next vowel or soft sign. Mastering the hard/soft distinction is crucial for good pronunciation, and it takes developing new articulatory habits – like learning how to speak all over again.

But enough about consonants. What about vowels? Are they really that unimportant for pronunciation? Spoiler alert: they matter more than you think, but not in the way you expect. I’ll write about it in the next article.

Stay tuned!