When I was working on a vocabulary list describing facial features, I realized that one word stood apart from all the others: beard, or борода in Russian.

The word itself is fairly common. Etymologically, the beard comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *bhar-dha, like English beard, German bart, French barbe, Spanish and Italian barba and so on. But in Russia, the beard has taken on a symbolic and even political significance. Here is the story.

For some, a beard is just facial hair, a fashion accessory. But as you may well know, in some cultures hair is sacred, and beards are cultivated for religious reasons. That was the case in Russia after the baptism of Rus’ c. 988. Russia converted to Orthodox Christianity, and according to the then concept of the Greek Orthodox Church, all men should have beards, the way God created them. And so, along with Orthodoxy, a ban on shaving beards was established throughout Russia. There are laws that forbid men to shave, and under these laws, anyone who violates this prohibition must pay very heavy fines. And so it went on for nearly seven centuries.

At the end of the seventeenth century, Peter the Great became Tsar of Russia. As a young man he traveled extensively in Europe and learnt from Europeans about new technologies. When he returned home, he decided to turn Russia into a European country. First he imposed a tax on beards, and then issued a special edict, which banned the wearing of beards, as well as the wearing and trading of traditional Russian clothing. Beards were chopped up with an axe, and those who refused to shave and change into European clothes were whipped and sent to hard labour.

There are several versions of why Peter the Great hated beards so much. According to one version, Peter was, in modern parlance, a Russophobe. He wanted to destroy everything traditionally Russian and thereby modernise the country. According to the second version, Peter saw in Europe that shaving was used to contain the spread of disease, especially in the army and navy. Peter needed a strong, healthy army and navy, so he ordered beards to be shaved. By the way, beards are still banned in many armies around the world, and certainly at the time such a ban was more than justified. Imagine, there were no effective hygiene products at the time. Beards were often infested with lice, and lice are carriers of diseases, including typhus. In Russia, the situation was even worse, because in that era, Russian utensils were very wide, and drinks often ended up on the beard. We even have a saying: “it flowed through the moustache and the beard, but not into the mouth” (По усам текло, по бороде текло, а в рот не попало). So there is a third version: Peter may have been insectophobic. There is some convincing evidence that he was terribly afraid of insects. And as you have already realised, a beard for insects is both a home and a restaurant. Peter simply could not stand the sight of boyars with lice and fleas crawling in their beards.

What Peter’s main reason was is not so important to us any more. The important thing is that since then the beard has become a symbol of the traditional Russian Orthodox way of life, and shaved chins have become associated with everything Western and anti-Russian. However, Orthodox books and canons have adapted to the new fashion – the chapters on the compulsory wearing of a beard have disappeared from them.

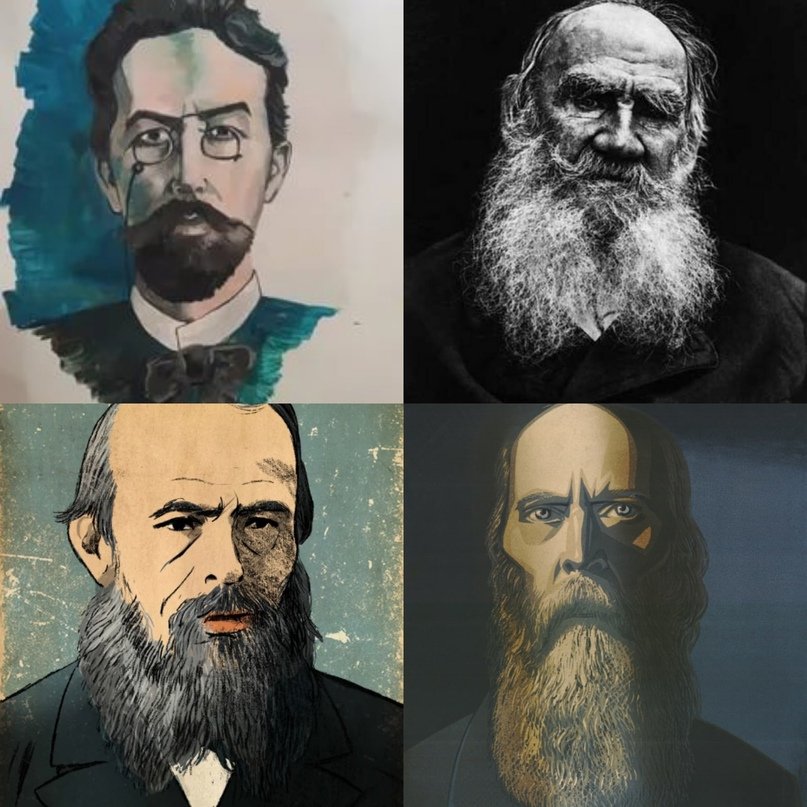

Throughout the nineteenth century, Russian intellectuals argued about whether or not Russia was part of European culture. The Westerners believed that Russia was part of Europe and that Russia’s development should go in a pan-European direction. Slavophiles insisted on the uniqueness of Russian culture and the need to preserve its traditions. Not surprisingly, Slavophiles demanded the return to fashion of beards as a symbol of Russianness. However, by the middle of the nineteenth century beards had become fashionable again in Europe, so almost all Russian classical writers, Slavophiles and Westerners alike, wore beards. It is hard to tell by the appearance of a beard whether this or that thinker or poet of the Silver Age was a Slavophile or a Westerner; beards were worn by both of them.

In Soviet times, a beard was considered a rather outdated accessory. A beard was associated with old age and perhaps illiterate peasantry. There is a saying about an old, well-known joke – шутка с бородой, or бородатый анекдот. It means, everyone has already heard that joke, and it is not funny anymore, i.e. the joke has been around for so long that it had enough time to grow a beard.

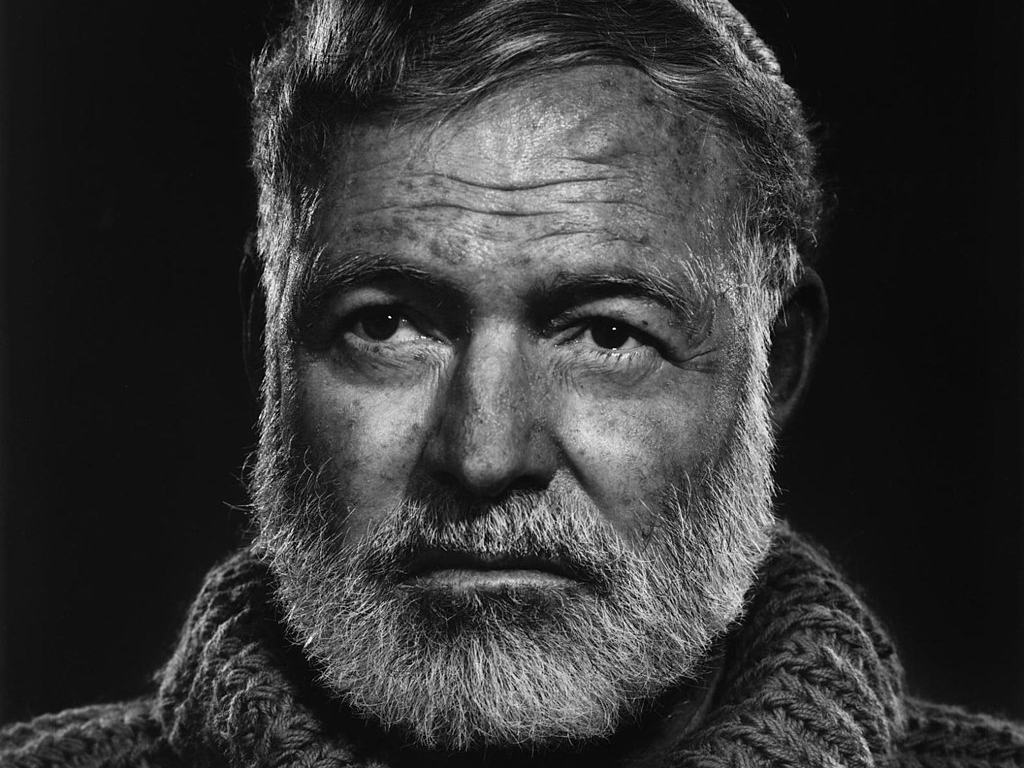

On the other hand, intellectuals, интеллигенция, tended to grow beards, especially in the 1960s, when the romance of conquering the wild and virgin forests of Siberia was on the rise. Somehow the beard gave a man a less formal appearance.

That’s how the cultural meaning of beard has changed over the centuries. I hope this short history lesson helps you remember the word.